Beethoven’s Razumovsky Quartets

A Radical Reinvention

A New Season, A New Vision

This season at the CMC Paris we’re diving into one of the most groundbreaking moments in Beethoven’s career: the Razumovsky Quartets. These three quartets not only mark a new phase in Beethoven’s musical journey—they also reinvent what chamber music could be. To fully understand their power and importance we’ll trace the journey from Beethoven’s early influences to his transformation in a radically individual voice. And on 28 March 2026, you can join us live in Paris for a performance of his first quartet of his middle period.

Beethoven’s Three Periods

More than any other composer, Beethoven’s creative life is traditionally divided into three periods: early, middle, and late. Each stage reflects profound changes in both his personal life and his musical language.

In the early period, Beethoven’s music draws heavily on the classical models of Haydn and Mozart. Whilst he used their works as a foundation, even these early compositions are unmistakably stamped with Beethoven’s emerging voice.

His middle period marks a dramatic departure from the past. Often called the “heroic” period, this phase features a new intensity, a deepening of personal expression, and a revolutionary expansion of musical form, structure, and harmony.

The late period is more introspective. Here, Beethoven pushes the boundaries of structure and delves into spiritual and philosophical depth, crafting music that often feels otherworldly.

Whilst Beethoven reimagined many genres—symphony, sonata, concerto—his string quartets most clearly show the evolution of his voice across these three periods. Understanding this progression helps us appreciate how intimately Beethoven’s personal and artistic struggles are woven into his music.

The Turning Point: Heiligenstadt Testament

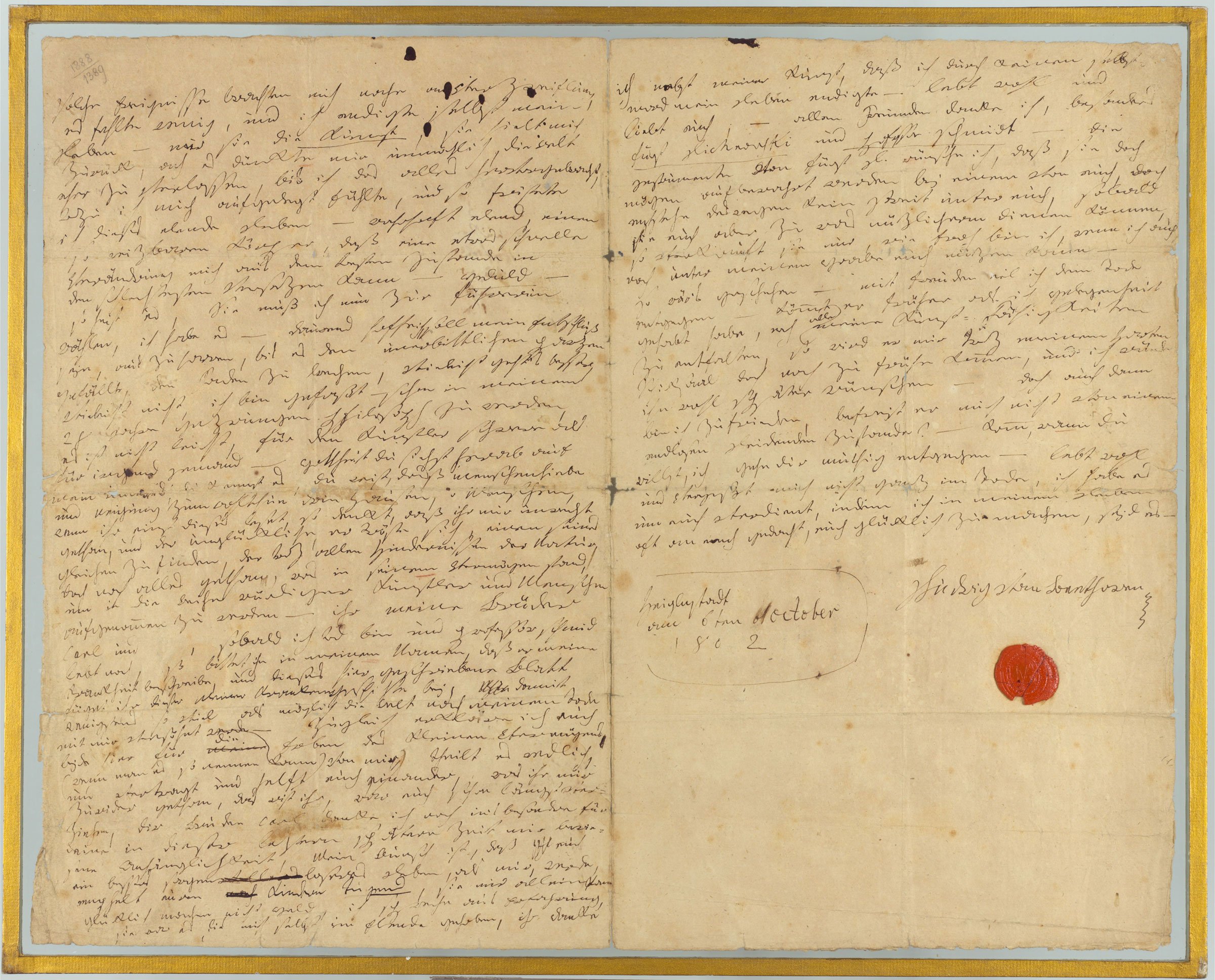

In 1802, Beethoven wrote a deeply emotional letter to his brothers known as the Heiligenstadt Testament. In it, he confronts the devastating effect of his deafness:

Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament

“Oh! You men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you…For six years now I have been hopelessly afflicted, …finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady…I was soon compelled to withdraw myself, to live life alone. If at times I tried to forget all this, oh how harshly was I flung back by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing… Such incidents drove me almost to despair, a little more of that and I would have ended my life—it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me.”

As musicologist Joseph Kerman writes, “this famous document reads less as a letter or a will than as a great apology, self-justification, self-pity, pathos, pride, hints of suicide, and presentiments of death.” But the Testament is more than a cry of despair—it marks a turning point. It awakened in Beethoven a realisation about his role as an artist. He began to see himself not just as a composer, but as a prophet of a new artistic vision and a voice for humanity. He was no longer writing music to fit tradition—he was writing music that would reshape it.

A New Creative Ambition

Title page of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, at first dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte. Angered that Napoleon crowned himself Emperor, Beethoven furiously scratched his name out, as seen here.

After this crisis, Beethoven set out to create music of a scope and intensity never before imagined. The work that exemplifies this the most is his Third Symphony, the Eroica (Heroic), not only a “watershed” moment in Beethoven’s own development but a turning point for the entire classical music tradition. This symphony shattered expectations with its unprecedented length, emotional depth, and complexity. It expanded the symphony from elegant entertainment into a profound narrative of human struggle and triumph. Its bold harmonies, dramatic contrasts, and innovative structures challenged listeners and composers alike, transforming the symphony into a vehicle for personal and philosophical expression. After the Eroica, the very idea of what a symphony could be was forever changed—there was no going back. (links to video about Eroica)

Following the Eroica, Beethoven’s music entered what we often call his “heroic” style. But heroism for Beethoven was not merely triumphant; it was about struggle, conflict, endurance, and ultimate transcendence. This is a music that wrestles with hardship and emerges transformed, reflecting a deeply human journey.

Importantly, this transformation extended to Beethoven’s string quartets as well. As Kerman observes, these quartets “breathe in a different world,” marking a new level of complexity, emotional range, and architectural innovation.

The Razumovsky Quartets

Count Andrey Razumovsky, the Russian ambassador in Vienna, to whom Beethoven dedicated his 3 Op. 59 Quartets.

In 1806, six years after his first set of quartets (Op. 18), Beethoven composed three new quartets, Op. 59, dedicated to Count Andrey Razumovsky, the Russian ambassador in Vienna. These were no ordinary string quartets. Compared to his classical Op. 18 set, these works were longer, more complex, and symphonic in their conception. The first quartet alone is nearly double the length of its predecessors.

Beethoven reimagined the sonic possibilities of the string quartet. He made string instruments imitate brass, winds, and percussion. He created unexpected textures and colours through bold harmonies and instrumental innovation. And yet, despite their grand scale, these works retain the intimate, conversational quality at the heart of chamber music.

Writer and musicologist Maynard Solomon captured their depth beautifully:

“The [Razumovsky] quartets are interior monologues addressed to a private self whose emotional states comprise a variegated tapestry of probing moods and feelings. Sullivan glimpsed this when he wrote that in the middle-period orchestral work 'the hero marches forth . . . performing his feats before the whole of an applauding world. What is he like in his loneliness? We find the answer in the Razumovsky Quartets. It was on a leaf of sketches for these works that Beethoven wrote… ‘let your deafness no longer be a secret-even in art.’ Here, in these quartets, he will reveal his deepest feelings, his sense of loss, his pains and his strivings.”

Unsurprisingly, these quartets challenged audiences and performers alike at the time. The Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung described them as:

“Three new, very long and difficult Beethoven string quartets… The conception is profound and the construction excellent, but they are not easily comprehended.”

The musicians who premiered the works were confounded. Violinist Schuppanzigh complained of their difficulty. Cellist Romberg threw the music to the floor and stomped on it in frustration. Violinist Radicati bluntly said “[This is] not music.”

But Beethoven was unfazed, saying: “They are not for you, but for a later age.”

The Op. 59 Triptych: A Superstructure

Unlike his earlier set of six, Op. 59 comprises a unified triptych—three quartets conceived as an interrelated set. This overarching structure is expressed in various ways:

Key relationships subtly link the quartets to one another. For example, the second quartet (in E minor) surprisingly introduces F major, referencing the first quartet. Its final movement begins in C major (shocking for a piece in E minor), foreshadowing the third quartet’s key.

Formal innovation is abundant. Instead of the typical weight being placed on the first movement, Beethoven distributes significance more equally across all four movements. Remarkably, 10 of the 12 movements in the Razumovsky set are in sonata form, often in experimental hybrids—like the audacious Scherzo-Sonata in Op. 59, No. 1.

Fugue and fugato techniques run throughout, as do monumental development sections, each one stretching the quartet form further than ever before.

Finally, there is the Russian theme: the first two quartets incorporate literal Russian folk melodies as an homage to Count Razumovsky. The third doesn’t, but its slow movement has an exotic, Eastern flavour that evokes a similar spirit.

Conclusion: From Crisis to Creation

The Razumovsky Quartets mark a defining moment in Beethoven’s artistic evolution. Born from crisis and driven by a new vision, these works boldly expand the limits of chamber music. They are symphonic in scale, intimate in spirit, and prophetic in ambition. With them, Beethoven not only redefined the string quartet—he laid the groundwork for everything that would follow in the 19th century and beyond. In our next post, we’ll dive into the first of the three: Beethoven’s monumental Quartet in F major.

What about you—do you know the Razumovsky Quartets? Do they strike you more as bold experiments or deeply personal reflections? And which one is your favourite? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below. And don’t miss our next post, where we’ll dive into Beethoven’s radiant F major Quartet, the first of this groundbreaking set.